==============================================================

Abstract

This paper is a based on an extensive study of the available textual and visual data on a collection of didactic paintings employed by the Manichaeans throughout the 1400-year history of their religion. Known as Mani’s Picture or Picture-Book, these paintings were originally created in mid-third century Mesopotamia with direct involvement from Mani (216-276 CE) and remained preserved by being adapted to a wide variety of artistic and cultural norms as the religion spread across the Asian continent. The evidence on Manichaean didactic art fits well with the pan-Asiatic phenomenon of, what Victor Mair calls in his 1998 monograph, “picture-recitation,” or “story-telling with images.” Nevertheless, more than any other religion, the Manichaeans made use of images by attributing canonical status to them. This assured their preservation. By situating the Manichaean data in a broader art historical context, this lecture brings together evidence on the same phenomenon by other contemporaneous religious traditions (such as Eastern Christianity, Judaism, and most importantly Buddhism) in third-eighth century West Asia, eighth-twelfth century Central Asia and eighth-seventeenth century East Asia.

The use of didactic paintings to illustrate orally delivered religious teachings was a practice maintained throughout the 1400-year history of Manichaeism. Known as Mani’s Picture in the earlier sources and as Mani’s Picture-Book in later records, a collection of images that depicted the basic tenets of Mani are at the center of this study. These paintings were created first in mid-third century Mesopotamia with direct involvement from Mani (216-276 CE) and were later preserved by being copied and adapted to a wide variety of artistic and cultural norms, as the religion spread across the Asian continent. The surviving textual and pictorial evidence of Manichaean didactic art has never been collated and analyzed before, nor has it been assessed in light of non-Manichaean comparative examples. While the Manichaean practice of teaching with images is similar to the pan-Asiatic phenomenon of “picture-recitation” or “storytelling with images” studied by Victor Mair in 1988, more than any other religion, the Manichaeans institutionalized the use of their didactic images by attributing a canonical status to them. This aspect contributed to their preservation, albeit in slowly changing artistic forms.

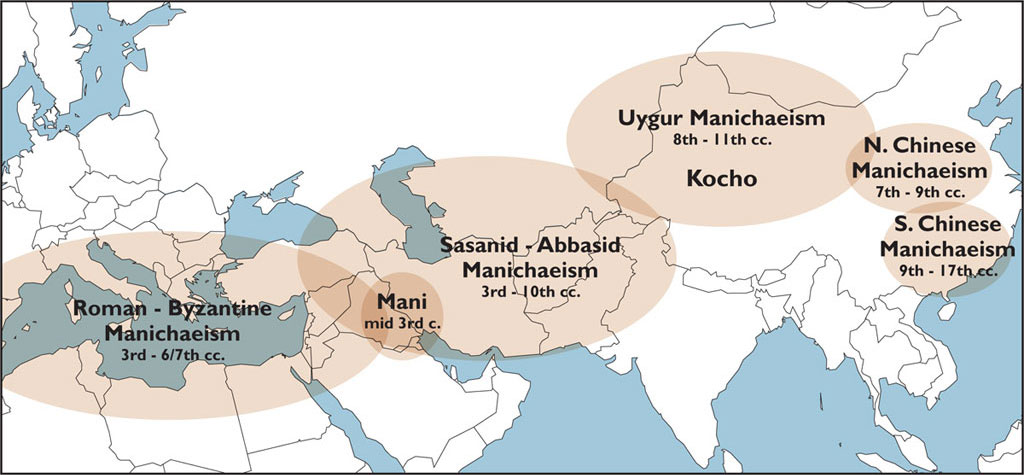

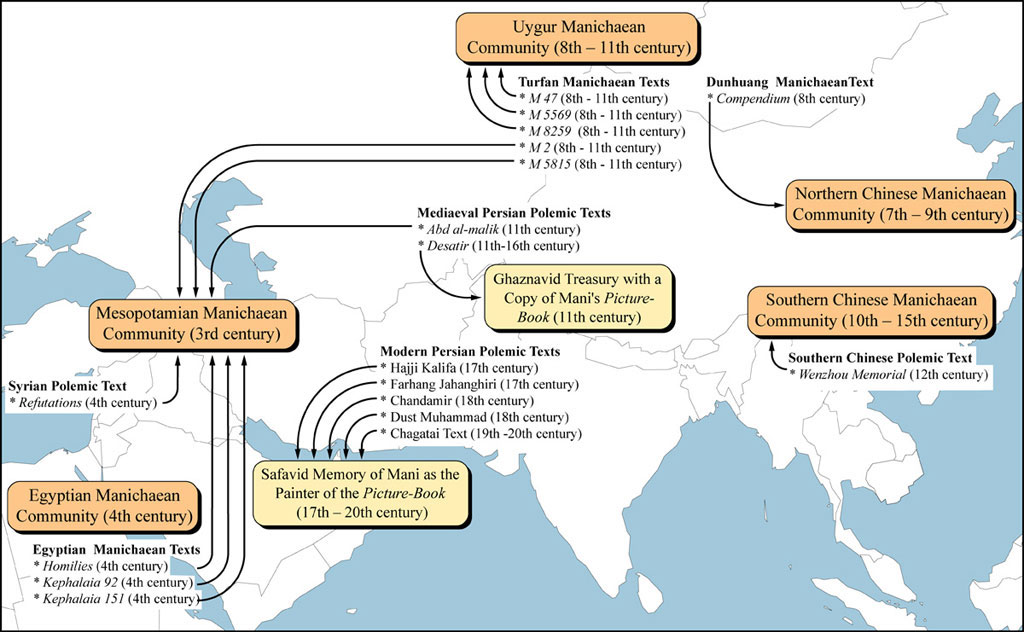

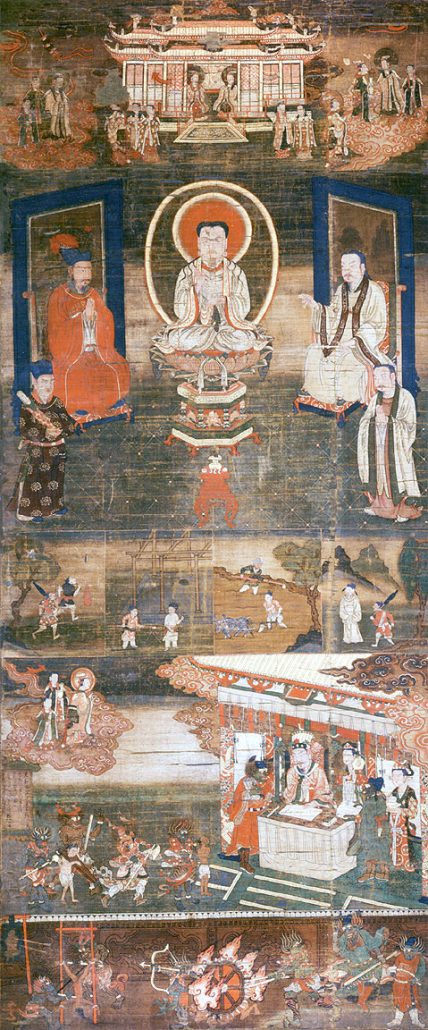

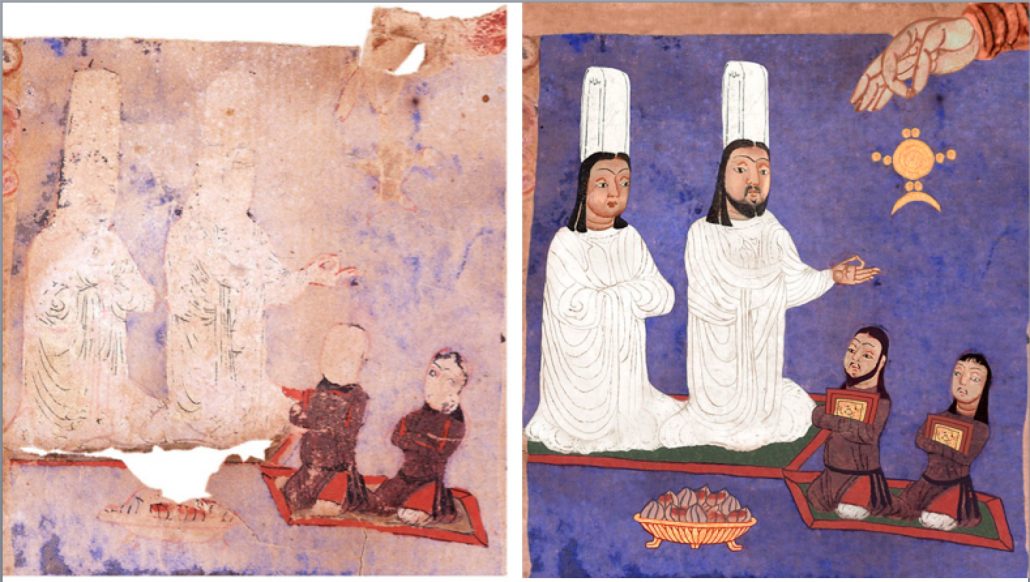

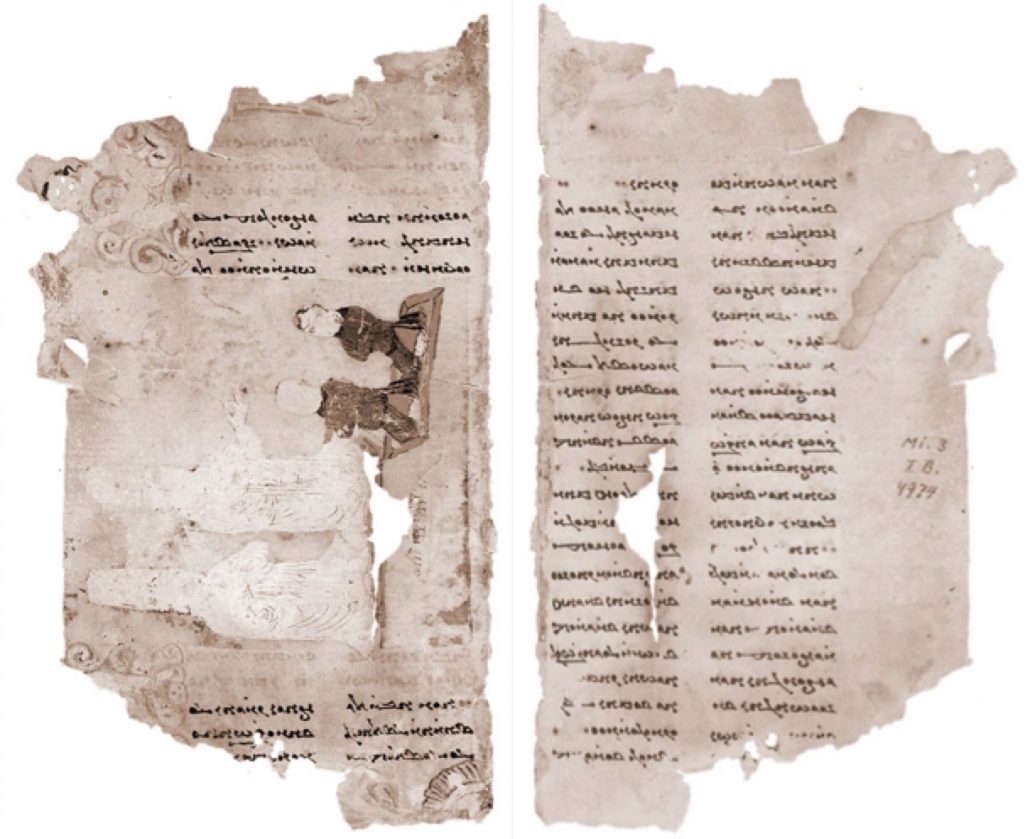

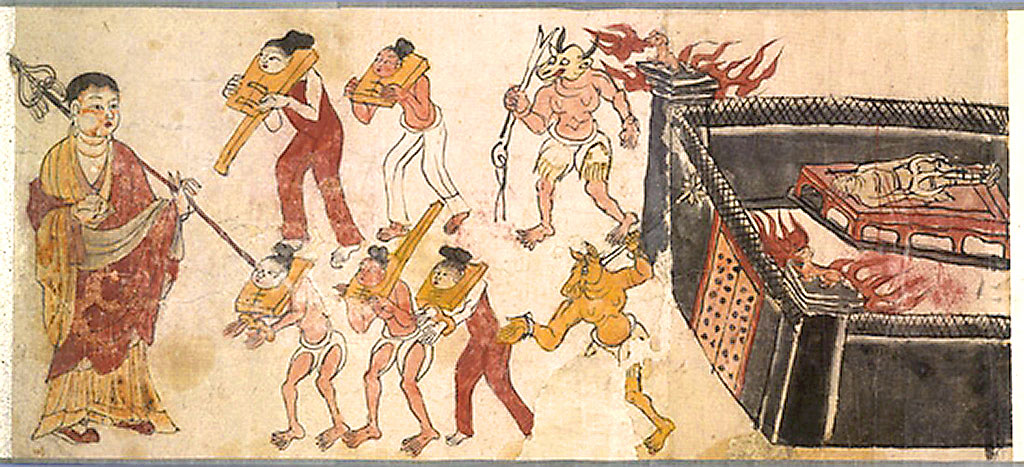

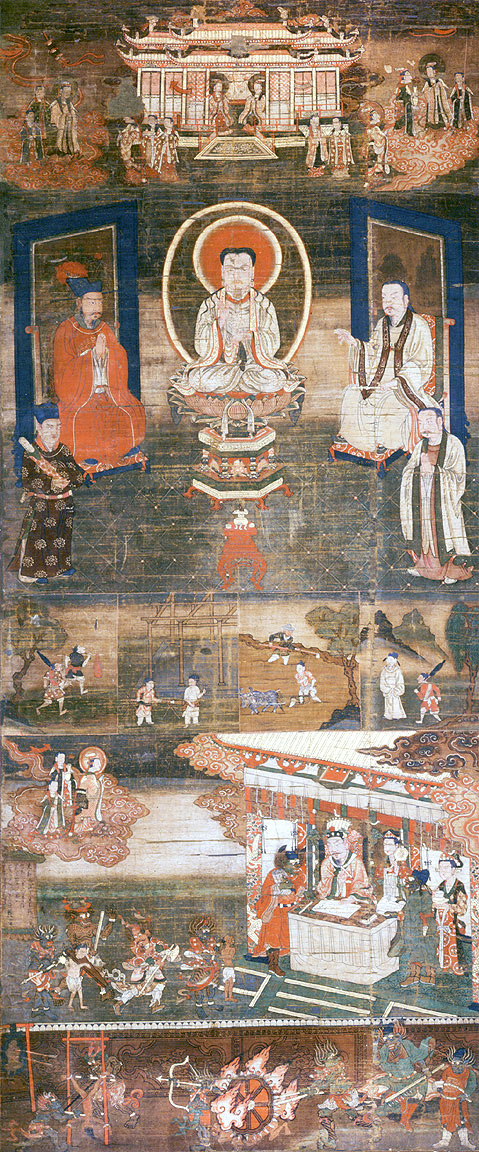

Already in its original vision, Mani’s religion is intended to be universal and thus “transcultural.” From its very start the Manichaean mission relied on multifaceted (oral, textual, and pictorial) means of communication that were meant to be adapted to a variety of distinct cultural contexts. Due to their nature, most oral means of communication remain undocumented, leaving us no chance to contemplate the culturally distinct verbal characteristics of religious speech acts. Rare exceptions to this are transcribed sermons or debates, in which the words of performances became texts and are studied as such. The transcultural nature of Manichaean texts is recognized today. As such, parts of Mani’s original third-century Mesopotamian Syriac (Eastern Aramaic) prose is preserved in Coptic translations from fourth-century Egypt, just as it is in Parthian, Middle Persian, Sogdian, and Uygur translations from tenth-century East Central Asia. While the language (vocabulary, grammar, and syntax) of Mani’s writings naturally changed in the course of the translation process, – the content was intended to be preserved -.as accurately as possible. I see analogous traits reflected among the remains of Mani’s Picture-Book surviving from ca. tenth-century East Central Asia and ca. twelfth- to fourteenth-century southern China. Although these paintings have just started to be identified and studied, it seems clear that, in course of their historical transmission originally from Mesopotamia to Central Asia and later from Central Asia to China, their subject matter (i.e. the core theme of this art) is conservatively preserved, while the pictorial language expressing that content is often visually “translated” in order to make the image comprehensible to the culture of its intended viewers. My current goal is to report on my research into Mani’s Picture-Book, the results of which form the basis of a monograph scheduled to be published in the Nag Hammadi, and Manichaean Studies series published by Brill.[2] My overall project is three-fold. It includes the study of the Manichaean textual sources, the identification and analysis of Manichaean pictorial sources, and the contextualized assessment of the findings under consideration of non-Manichaean comparative examples. By situating the Manichaean data in a broader context, my study brings together evidence of the practice of teaching with images in other contemporaneous religious traditions (such as Eastern Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and most importantly Buddhism) in third- to eighth-century West Asia, eighth- to twelfth-century Central Asia and eighth- to seventeenth-century East Asia. – Before discussing these three approaches, it may be useful to note some basic facts about the history of the Manichaean religion and its surviving artistic remains. Map 1: Phases of Manichaean history (3rd-17th centuries CE) (Source: Transcultural Studies). The overall history of Manichaeism is better understood today in light of research published in hundreds of articles and books during the past century.[3] An overview of the major phases that make up the history of Manichaeism can be illustrated in a map (Map 1). This religion originated in mid-third-century Mesopotamia from the teachings of Mani. From there it immediately spread to the west, where it was persecuted to extinction by the sixth and seventh centuries. Manichaean communities existed in Iran and West Central Asia between the third and tenth centuries. Spreading further east along the Silk Road, Mani’s teaching reached the realm of the Uygurs, whose ruling elite adopted it as their imperial religion between the mid eighth and early eleventh centuries. Appearing in China during the seventh century, Manichaeism was present in the major cities during the Tang dynasty (618–907), surfacing in the historical records as monijiao (“Religion of Mani”). For a brief period, which corresponded to the zenith of Uygur military might and political influence on the Tang, Manichaeism enjoyed imperial tolerance and was propagated among the Chinese inhabitants of the major urban area.[4] The fall of the Uygur Steppe Empire (840/841) was followed by- the persecution of all foreign religions in 843–845. As a consequence, Manichaeism disappeared from northern China. Its Chinese converts fled westwards to the territories of the Sedentary Uygur Empire (841–1213) in the region of Dunhuang and the Tarim Basin, and towards the southern part of China, where a fully sinicized version of the religion, referred to in Chinese sources as mingjiao (lit. “Religion of Light”), existed until the early seventeenth century.[5] During the twentieth century, Manichaean artistic remains were known to have come almost exclusively from East Central Asia, from the region of the oasis city of Kocho, which was a trading and agricultural center along the northern Silk Routes. For approximately three centuries, it also functioned as the winter capital of the Sedentary Uygur Empire. German expeditions excavated Kocho prior to World War I and rescued about 5000 Manichaean manuscript fragments and a cache of artistic remains. The resulting publications lead to the scholarly début of the topic of Manichaean art in art history during the 1910s and 1920s.[6] During the past twenty-five years, a new understanding of Uygur Manichaean art emerged based on the identification of an Uygur Manichaean artistic corpus: the classification and scientific dating of its painting styles, the analytical study of its book medium (i.e., codicology), and the continued research of its iconography. Criteria for identifying a corpus, which doubled the number of Manichaean remains to 108, were put forward in 1997, and formed the basis for a 2001 catalogue featuring color facsimiles and critical editions of all associated texts.[7] A survey of this corpus revealed that the pictorial remains exhibit two locally produced painting styles: one with Western roots, dubbed “the West Asian style of Uygur Manichaean art,” which appears almost exclusively on remnants of illuminated books in codex and scroll formats; the other with Eastern roots, designated “the Chinese style of Uygur Manichaean art,” which was found mainly on temple banners, textile displays, and wall paintings. Contrary to previous assumptions -, carbon dating combined with stylistic analysis and historical dating reveal that both styles existed during the tenth century. This insight confirms that artists working with distinct techniques and media were employed simultaneously in Kocho.[8] The most numerous component of this corpus, the fragments of illuminated manuscripts, were subjected to a codicological analysis in a 2005 monograph that assessed the formal aspects, as well as the contextual cohesion of text and image.[9] Although a monograph on Manichaean iconography has yet to be completed, a series of insightful studies have been appearing since the early 1980s.[10] Recently, an exquisitely well-preserved group of Manichaean paintings that originated in southern China have been identified in Japanese art collections.[11] As a result, a growing corpus of seven Chinese Manichaean paintings is known today. They are silk hanging scrolls that portray explicitly Manichaean subjects conveyed in a contemporaneous local artistic style. They were made and used in southern China sometime between the twelfth and the fifteenth centuries and subsequently taken to Japan, mostly due to Japanese interest in collecting Chinese pictorial art. The ongoing studies of these paintings will undoubtedly reveal a wealth of new information and thus improve our current understanding of the overall history of Manichaean art, specifically Chinese Manichaean art, as well as that of Mani’s Picture-Book. Manichaean textual sources on the use of didactic art The comprehensive critical analysis of the known Manichaean textual sources provides the foundation of this study. Currently eighteen textual sources are known that refer to Mani’s Picture-Book (Map 2). Each of these texts is about a paragraph in length and originated in divergent contexts from throughout the Manichaean world. Although many of them have been noted in previous scholarship, they have never been studied as a group, nor have they been subjected to a systematic analysis that allows us to collect and assess their data as a whole in order to better understand the history of these unique Manichaean works of art. Map 2: Existence of Mani’s Picture-Book as documented in eighteen textual sources (Geographical distribution and dates) (Source: Transcultural Studies). Even the most basic statistical assessment of the distribution of these texts reveals important facts about the history of Mani’s Picture-Book (Map 2). In terms of their religious contexts of origin, 50% are primary Manichaean texts —surviving from the deserts of Northeast Africa (3 texts) and East Central Asia (6+1 texts),—which confirms the continued use of the Picture-Book among the followers of Mani. The other 50% of the texts derive from polemical accounts, including Christian texts in West Asia (1 text), Persian Islamic texts from West and Central Asia (2+5 texts), and an official government report from southern China (1 text), suggesting that this Manichaean collection of didactic paintings was of interest to rival religious and secular authorities alike. Regarding their geographical and chronological distribution, over 40% of these texts (8 texts) discuss the use of Mani’s Picture-Book in third-century Mesopotamia, and among the Uygurs between the eighth and early eleventh centuries. With decreasing significance, Chinese use is also confirmed initially in the North, in the capital cities of the Tang dynasty, and later in the South, in the coastal Fujian province between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries (2 texts). Persian sources that specifically mention Mani’s Picture-Book and not merely “Mani the painter” are also included in this survey. Starting from the eleventh century, these sources reflect a Persian (non-Manichaean) admiration for Mani’s Picture-Book (2 texts). More recent Persian accounts, dating from the past 300 years, preserve the memory of Mani’s Picture-Book in various literary genres (5 texts). Through their temporal and geographical distribution, these eighteen texts reflect the gradually diminishing use of the Picture-Book, confirming its strong presence in West Asia (4 texts) and East Central Asia (5+1 texts) during the early and the middle era of Manichaean history, and a lessened prominence during the late era of this religion in East Asia (1 text). An example of what the critical analysis of each text entails can be illustrated with one of the most informative early sources on the Picture-Book, written by Ephrem Syrus (d. 373 CE). Ephrem mentions the Manichaeans’ use of didactic images in Syro-Mesopotamia in a passage of his Prose Refutations.[12] Dating from sometime in the middle of the fourth century, Ephrem composed this text to refute Marcion, Bardaisan, and Mani who propagated their rivaling version of Christianity in West Asia. Despite its polemical tone, the Prose Refutations are especially relevant, since Ephrem lived within a century of Mani and shared with him a common language and cultural background. Equally significant is that Ephrem quotes directly from a Manichaean text and credits Mani’s disciples as his source of information. Specifically on the practice of teaching with images, he writes: “According to some of his disciples, Mani also illustrated (the) figures of the godless doctrine, which he fabricated out of his own mind, using pigments on a scroll (Syr. megillah). He labeled the odious (figures) ‘sons of Darkness’ in order to declare to his disciples the hideousness of Darkness, so that they might loathe it; and he labeled the lovely (figures) ‘sons of Light’ in order to declare to them ‘its beauty so that they might desire it.’ He accordingly states: ‘I have written them (the teachings) in books and illustrated them in colors. Let the one who hears about them verbally also see them in visual forms (Syr. yuqnâ, ‘image’ or ‘picture’), and the one who is unable to learn them (the teachings) from [words] learn them from picture(s) (Syr. tzwrt, ‘picture’ or ‘illustration’).”[13] Ephrem records here that the Manichaeans had a collection of images to illustrate their teachings from the very beginning of their history. He credits Mani with its authorship. Further, he also confirms the doctrinal content of these paintings by stating that they capture Mani’s “doctrine” and “the teachings.” He refers to the latter with plural pronouns, because Mani’s doctrine consisted of a collection of teachings. Ephrem also conveys that the teachings were “illustrated” “in pigment,” “in colors,” “in a visual form,” and that they were “pictures.” The Syriac tzwrt (“picture”, “illustration”) is used here as a collective noun that John Reeves translates as “picture(s)” in his 1997 edition of the text. The use of the plural in English is justified by the Syriac context. The terms “doctrine” and “picture” both function as collective nouns. Just as we cannot imagine Mani’s doctrine to be one teaching, but rather a collection of teachings, the art that captured Mani’s doctrine was most certainly not a single image, but a collection of images, which Ephrem knew as a scroll (Syr. megillah), the format of which is well suited for storing a collection of individual scenes.[14] With Ephrem’s passage in mind, it would be wrong to assume that Mani aimed his paintings specifically at an illiterate audience while his texts were meant for the literate members of his community. The vast majority of people listening to any religious teaching in late ancient Mesopotamia were illiterate. Illiteracy, however, does not seem to be the point here. Instead, Ephrem states that these images supplemented oral teachings, which were an intrinsic part of Manichaean instruction to any and all audiences. The paintings were designed to be seen by those “who hear the teachings verbally” and who are “unable to learn them just from the words.” Such teachings were delivered orally in an environment where the paintings played an essential role. They captured the content of the teaching in a medium different from that of the spoken word, by visual means, in order to make comprehension easier for the audience.[15] In other words, these paintings were didactic pictorial displays and the Manichaean tradition of using them began with Mani himself in mid-third-century southern Mesopotamia. Other texts confirm its continued use throughout the history of this religion. As a group, the eighteen texts on the Picture-Book constitute a rich documentary source regarding the names, formats, and materials of this work of art, which understandably changed over time.Regarding the history of the name of the collection,early textual sources record it as the Picture (Syr. tzwrt and yukna, Copt. hikon, Gr. eikon, Parth. ārdahang, and MPers. nigar), while later texts from China and Islamic Persia call it the Picture-Book (Chin. tu-ching and Pers. nigarname). Until recently, the latter term dominated modern scholarship. I prefer to use it myself, because it better conveys the idea of a “collection of paintings” and thus avoids the misleading “single image” connotation. In regard to its formats and materials, the texts document that Mani’s Picture-Book existed in both book and textile formats. “Picture-books” are noted in both scroll and codex formats, suggesting a horizontal scroll most likely made of parchment in late ancient West Asia (containing a series of individual scenes painted next to one another) and a horizontal codex that was probably made of paper in mediaeval Central Asia (with full page images on folia bound along their shorter side). In addition to such book formats, there are also documented those that we may call “pictorial cloth displays”. It seems that they were portable didactic tableaux (that featured images on the surface of a cloth hanging scroll). Examples survived in both painted and embroidered formats among the Uygur and Chinese Manichaean artistic remains. Some of the texts convey that Mani’s Picture-Book was listed among the canonical works of the Manichaean religion. They state that in addition to books written by Mani, the Manichaean canon includes a solely pictorial doctrinal work—a collection of didactic paintings attributed to Mani.[16] None of the canonical Manichaean books survive intact, not even in later copies. Only smaller fragments that were produced as translations are known today. As the two most important records of Mani’s teachings, the Picture-Book is frequently singled out with the Gospel in West Asian sources. These two works from the Manichaean canon are used as symbols for the textual and visual records that Mani created specifically to prevent the corruption of his teachings. Accordingly, theses two books are named in a ten-point list of claims for Manichaean superiority in Kephalaion 151, where Mani states: “My church is superior in the wisdom and [the secrets?], which I have revealed to you in it. As for this [immeasurable] wisdom I have written it in the holy books–in the great [Gospel] and the other writings – so that it not be altered [after] me. Just as I have written it in books, so [I have] also ordered it (keleuein) to be drawn (zōgraphein). For all the [apostles], my brothers, who have come before me, [have not written] their wisdom in the books as I have written it. [Neither have] they drawn their wisdom in the Picture (hikōn) as [I have drawn] it. My church surpasses the earlier churches [also in this point].”[17] The survey of the textual sources confirms that, in addition to writing, painting was employed as a tool by Mani to clearly communicate and at the same time avoid any adulteration of his teachings. No other religious prophets, including Zoroaster, Shakyamuni, and Jesus (“my brothers, who have come before me” – as Mani calls them in Kephalaion 151), wrote down, let alone painted their teachings. Mani saw this as an important distinction between him and these predecessors. Just as in canonical texts, copies of Mani’s collection of didactic paintings were also routinely made, assuring its preservation across the phases of Manichaean history, a point that I will revisit below.[18] Manichaean Pictorial Art with Didactic Themes A total of twenty-five Manichaean paintings can be identified today from East Central Asia and southern China that feature didactic subjects depicting core Manichaean teachings. I argue that the pictorial themes of these scenes were originally part of the collection of images known as Mani’s Picture-Book. These twenty-five pictorial sources constitute two distinct groups. The primary group is formed of actual paintings of Mani’s Picture-Book. Some of these are intact, while others are fragmentary scenes (large enough to be identified) conveyed either in picture-book formats (pictorial scroll and pictorial horizontal codex) or textile display formats (painted or embroidered silk hanging scrolls). The second group consists of copies of the Picture-Book‘s scenes preserved as illuminations in Manichaean hymnbooks and sub-scenes painted onto Manichaean funerary banners. Sermon on Mani’s Teaching of Salvation Chinese Manichaean silk painting, complete hanging scroll, 142 cm x 59,2 cm, colors on silk, ca. 13th century, Yamato Bunkakan Museum, Nara, Japan (Source: Transcultural Studies). Note the Five registers from top to bottom: Register 1. The Light Maiden’s Visit to Heaven. The Stages of the Visit: 1. Greetings by the host upon arrival, 2. Meeting with the host in the Palace, 3. Farewell to the host; Register 2. Sermon Performed Around the Statue of a Manichaean Deity (Mani); Register 3. The States of Good Reincarnation. Four Classes of Chinese Society: 1. Itinerant workers, 2. Craftsmen, 3. Farmers, 4. Aristocrats; Register 4. The Light Maiden’s Intervention in the Judgment after Death; Register 5. States of Bad Reincarnation. The Tortures of Hell: 1. Person shot with arrows, 2. Person sawed in two, 3. Person crushed by a fiery wheel, 4. Demons waiting for their prisoner. An example of a well-preserved scene from the Picture-Book has been recently identified. It is a Chinese silk painting in the collection of the Yamato Bunkakan, in Nara, Japan, dating sometime between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Figure 1). The Manichaean origin of this painting was first suggested by Takeo Izumi on the basis of a comparison with the Mani statue, and later affirmed by Yutaka Yoshida.[19] This 142 centimeter tall hanging scroll is accompanied by a dedicatory inscription with an illegible date that offers this painting “to a temple of vegetarians.”[20] The painting itself consists of five clearly demarcated registers of varying heights that together convey a subject that we may call Sermon on Mani’s Teaching of Salvation.[21] At the top, the first register depicts heaven as a palatial building that forms the focus of a narration of events with the repeated images of a few mythological beings. Using continuous narration, this composition shows how the Light Maiden and her entourage conduct their business: arriving on the left while being greeted by an unidentified female host; visiting the host while seated inside the palace (center); and then departing on the right while being seen off by the host. The scene may be titled The Light Maiden’s Visit to Heaven. The second register depicts a sermon performed around the statue of a Manichaean deity (most likely Mani) by two Manichaean elects, shown on the right.[22]The elect giving the sermon is seated, while his assistant is standing. A layman and his attendant, seen on the left, listen to the sermon. Therefore, the scene may be titled Sermon around a Statue of Mani. The third register is divided into four small squares, each devoted to one of four classes of Chinese society in order to capture what seems to be the daily life of the Chinese Manichaean laity (known as “auditors”). In succession from left to right, the first scene represents itinerant laborers; the second—craftsmen; the third—farmers, and the fourth—aristocrats.[23] This set of scenes may be titled States of Good Reincarnation. The fourth register depicts the Manichaean view of judgment after death. It shows a judge seated behind a desk surrounded by his aides in a pavilion on an elevated platform, to the front of which two pairs of demons lead their captives to hear their fates, either positive or negative. In the upper left corner, the Light Maiden arrives on her usual cloud formation with two attendants, to intervene on behalf of the man about to be judged. This scene may be titled The Light Maiden’s Intervention in a Judgment. The fifth register concludes the hanging scroll by portraying four fearful images of hell that include from right to left: arrows being shot at a person suspended from a red frame, dismemberment, a fiery wheel rolled over a person, and lastly a group of demon torturers waiting for their victim. This scene may be titled States of Bad Reincarnation. Clearly influenced by the iconography of local Buddhist artistic themes, all but one of the scenes look analogous to contemporaneous Buddhist works of art, including heaven on top and judgment and hell on the bottom. Nevertheless, the reoccurring figure of the Light Maiden in these scenes, as well as the uniquely Manichaean, centrally located, and largest Sermon Scene, makes this a readily identifiable Manichaean work of art. Scroll Fragment (MIK III 4947 & III 5d) with an image of the Buddha, Museum of Indian Art, Berlin (Source: Transcultural Studies). Fragmentary scenes that nevertheless preserve enough data to identify their actual didactic contents, may also be identified as examples of Mani’s Picture-Book. One such scene is found on a paper handscroll depicting the Primary Prophets from Kocho (MIK III 4974 & III 5d) in the collection of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Figure 2).[24] This fragment was identified as Manichaean based on the correlation with specific motifs and technical details of Manichaean art.[25] This torn piece of lavishly painted paper retains parts of the central being’s mandorla and one of the original four prophets, the historical Buddha (Figure 2a). Shakyamuni is shown in authentic Buddhist iconography and is identified by the word “Buddha” written vertically on his chest in the Parthian language (“B-U-T”) and the Sogdian script.[26] This Buddha figure belonged to the upper right section of a scene that was originally painted on a horizontal scroll (Figure 2b). The original composition was organized around the still-intact large central figure (Mani)beneath a canopy. It probably involved, in the section now lost, the other three of the four figures (forerunners to Mani), including Jesus. This fragment derives from a pictorial didactic diagram with a uniquely Manichaean theme, whichwe may call the Primary Prophets. It was based on Manichaean texts from West and East Central Asia discussing this topic. In these texts, Mani is mentioned along with the founders of other religions whose teachings were relevant to Manichaeism. The East Central Asian versions of the texts name four other prophets, all of whom are considered to be of a lesser rank than Mani. They include the antediluvian prophet, Seth; the Buddhist prophet, Shakyamuni; the Zoroastrian prophet, Zarathustra; and the Christian prophet, Jesus. Analogously, the two pictorial fragments from Kocho feature five figures arranged in a symmetrical composition that uses centrality and scale to communicate hierarchy—the four somewhat smaller figures, symbolizing the forerunners, surround a larger central figure, most likely Mani.[27] During the East Central Asian (Uygur) phase of Manichaean history, some scenes of the Picture-Book were copied to other media and thus survived as scenes on temple banners or illuminated manuscripts discovered in Kocho. I argue that such scenes can be identified based on their didactic pictorial contents, since they depict core Manichaean teachings that are well documented from textual (often canonical) sources. In the case of book paintings, the lack of contextual cohesion (i.e., the lack of harmonized content between the texts and image) and the sideways orientation of the painting in relation to the writing suggest that the paintings originally had a solely pictorial didactic context (such as a “picture-book”). Their scenes developed independently from the illuminated “text-book” during the early, West Asian phase of this religion. The Work of the Religion Scene (MIK III 4794 recto, detail), before reconstruction (at Left, Gulasci, 2009) and after digital reconstruction (6.6 cm x 6.1 cm) (at Right, Gulasci, 2009) (Source: Transcultural Studies). An example of a scene that, I suggest, originated as part of Mani’s Picture-Book, is the “Work of the Religion” scene preserved on the recto of a torn codex folio (MIK III 4974) from the collection of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Figure 3). The surviving content of the painting (Figure 3a) becomes more understandable with a digital, non-interpretive, reconstruction of the same scene (Figure 3b). The steps of this reconstruction were discussed in a recent publication.[28] This painting is a didactic diagram that explains the goal of Manichaean practice: The Freeing of the Light from the Captivity of the Darkness.(1) Laypeople donate vegetarian food (that is believed to have a high concentration of light particles) to the elect (the priesthood).(2) After consuming this food, the bodies of the elect free the ight.(3) Through the singing of hymns, light departs from the bodies of the elect and heads towards to the Realm of Light. (4) The moon and sun act as vessels of the light, transporting the freed light particles back to God (to the Realm of Light). (5) God, i.e., “the Father of Greatness” (symbolized here by his right hand) reaches into the scene from above to receive the shipment.Even when viewing the original painting without the reconstruction, all details of this iconography can be identified in Manichaean texts that discuss “The Work of the Religion.” This scene depicts a core teaching and is free from East Central Asian (Buddhist) influence. Therefore, it is most likely that this pictorial subject originated among the scenes of Mani’s Picture-Book. Turfan Manichaean Illuminated codex Folio, MIK III 4974, (Gulacsi, 2005, Fig. 5/8)(Source: Transcultural Studies); recto of paper fragment (at left) and verso of fragment (at Right). In addition to the didactic theme of this painting (i.e., the liberation of light from the captivity of darkness), distinct from the text of the folio (benediction on the leaders of the local Uygur community), it is the physical context of the image that preserves codicological clues that suggest a solely pictorial source of origin. I hypothesize that the painting survived as a replica of a picture-book scene, copied onto a manuscript folio with a Middle-Persian language text, which is a benediction of the sacred meal and the leadership of the local community. The benediction text continues on the verso. The layout of this folio (like that of many other Manichaean fragments) can be fully reconstructed. As this reconstructed page layout shows, the writing utilizes the codex page vertically, while the painting utilizes the same page horizontally. The text does not comment on the painting and, vice-versa, the image does not make a visual reference to the text. I can only interpret this dual discrepancy by suggesting that they were not developed together within the illuminated book, but were instead derived from two independent sources: the texts came from a Manichaean textual tradition, while the images from Manichaean pictorial art. Teaching Manichaean doctrine with the aid of both texts and images takes us back to Mani himself, who was active in a multicultural part of the world under Sasanid rule in southern Mesopotamia. Regarding the texts left behind by Mani, it is known that he was highly literate in several languages and composed and committed himself to writing a significant portion of the Manichaean canon. Mani viewed his literacy as an important point of distinction between him and the founder of other religions. In regards to the paintings, a variety of textual sources note that Mani commissioned or painted images himself that captured his teaching in a visual form. The two originally separate means of communication (textual and pictorial) remained important in later Manichaeism and in some cases became combined in a third, new medium (illuminated manuscripts adorned with —horizontally arranged images), which the Manichaeans seemed to employ only during the East Central Asian phases of their history.[29] Comparative Sources on Teaching Religion with Images across the Asian Continent Manichaean communities were not the only religious traditions active across the Asian continent and known to have illustrated the oral instructions of their teachings with didactic art. In 1988, Victor Mair from the University of Pennsylvania devoted a monograph to what he called “picture recitation” or “story telling with pictures”; the book features both secular and religious examples of the practice.[30] The starting point of Mair’s research was a genre of popular Chinese literature, known as bian-wen (transformation texts). Dating from the Tang period, transformation texts represent the first extended vernacular narratives in China. The earliest examples discovered from Dunhuang included textual manuscripts, as well as painted hand scrolls, sometimes with no texts, just images, which contributed to a confusion regarding the interpretation of their function and origin. According to a popular explanation, they were promptbooks for monks’ sermons and lectures. At the same time, evidence suggested that pien-storytellers were primarily lay entertainers (sometimes women). Mair argued that the genre of transformation texts derived from the tradition of chuan-pien, a type of oral storytelling with pictures, i.e., picture recitation, which as a folk tradition in China was poorly documented in historical accounts. Since relatively little Chinese data was available on picture recitation, Mair considered analogous genres from a variety of countries across the Asian continent, including India and southeast Asia, Iran and Central Asia, as well as Japan. Through his survey Mair could point to the historical depth of the tradition, as well as its diverse religious application, not only among Buddhist, but also Hindu, Jain, Islamic, and Manichaean communities. Teaching with pictorial scrolls in Etoki performances of contemporary Japan; Pointing to scenes of a hanging scroll, Etoki performance at Saiko-ji, Nagano Prefecture, Japan, (Kaminishi, 2006, Fig. 5/2) (Source: Transcultural Studies). The best contemporary examples of the use of images to illustrate oral instructions of religious teachings are found in Japanese Pure Land Buddhist temples. With the spread of Buddhism from China to the rest of East Asia, the practice of picture recitation was transmitted to Japan, where it still exists today in the form of etoki performances. The fist monograph in English on the Japanese etoki appeared in 2006. The author, Ikumi Kaminishi, presented a contextualized study that focused on both textual and visual documentary sources, some dating as early as the 10th century. Teaching with pictorial scrolls in Etoki performances of contemporary Japan; Moving between scenes of hand scroll. Etoki performance at Dojo-ji, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan, (Mair, 1988, color plate 6) (Source: Transcultural Studies). Since etoki is still offered today in about two dozen Buddhist temples, Kaminishi is able to introduce data based on documentary textual and visual sources, actual paintings currently used for the practice, and participant observation. The latter allows the reader to see the survival of specific didactic techniques that utilize pictorial hanging scrolls (vertical textile paintings) and handscrolls (rolled picture-books) as visual displays.[31] Japanese Buddhist sources of picture recitation may help the interpretation of the surviving, fragmentary data provided by Manichaean sources from southern China and East Central Asia. On the one hand, the Buddhist analogies document that teaching with images can be done either in a folk setting by laymen, or in the institutional setting of an organized religion by monks for the benefit of the laity. On the other hand, they allow us to see that both pictorial handscrolls (rolled picture-books) and hanging scrolls (vertical textile paintings) are suitable formats for didactic visual displays. The vertical format of the hanging scroll allows the viewer to see a large number of scenes at the same time, the viewing order of which is given by the instructor, who points to the individual scenes as the instruction progresses. The horizontal format— of the hand scroll—prevents the viewer from seeing the entire roll surface simultaneously. Instead, it is customary to view only a couple of scenes at the time. In this case, the viewing sequence is defined by the horizontal layout of the scenes, which is right to left in East Asia. Wall painting depicting the showing of a cloth with the Four Major Events, Kizil, ca. 7th century, Museum of Asian Art, Berlin, (Mair, 1988, Plate IV) (Source: Transcultural Studies). The use of these two formats (i.e., vertical hanging scroll and horizontal handscroll), like the two materials (i.e., painted silk and painted paper) are documented for the Buddhist communities of medieval East Central Asia, who also employed them for conveying didactic pictorial subjects. A version of a vertical textile display depicts the four major events from the Life of the Historical Buddha, which is preserved on a wall painting from the caves of Kizil, dating from the 8th century CE (Figure 6a). A solely pictorial paper roll depicting the Ten Kings of Hell is preserved in Cave 17 at Dunhuang, dating from tenth-century, and housed today in the collection of the British Museum (Figure 6b). Pictorial paper scroll depicting the Ten Kings of Hell (details), Dunhuang, ca. 10th century, British Museum, London, (Whitfield, 1988, Fig. 26) (Source: Transcultural Studies). These Buddhist examples are particularly noteworthy, because they derive from a time and place where the Manichaeans were also known to have rendered the images of their Picture-Book in analogous pictorial formats and materials, in order to illustrate the most important teachings of their tradition. The use of paper in Buddhist and Manichaean art is first documented in East Central Asia. While a few illuminated Manichaean parchment fragments do survive from Kocho,[32] paper clearly dominated the productions of books and picture-books in both codex and scroll formats. East Central Asia is known for religious and artistic innovations that defined the subsequent formation of these two traditions. The existence of didactic pictorial art and the employment of oral instruction are already confirmed for the pre-East Central Asian phase of their history. The earliest surviving remains of Buddhist didactic art derive from the area of the Kushan Empire, when much of Central Asia and Northern India were encompassed under the rule of an Indo-European speaking nomadic people between the 1st and 3rd centuries (Map 3). The era of the Kushan Empire is especially relevant for this study, not only because during its reign the first narrative images of the Buddha’s life were created, but also because the last century of Kushan rule is contemporaneous with Mani, who had ties with northern India. Although Mani spent most of his life within the western regions of Sasanid Iran, he is known to have led a mission along the eastern frontiers of Iran into what today is northwest India (just south of what belonged to the Kushan realm), where he encountered Buddhist and Jain communities.[33] One of the most important subjects of Buddhist art, the narration of the life of the historical Buddha, is first documented in the Kushan era. Extensive stone relief carvings of the life of the Buddha that survived from the region of Gandhara (today Pakistan and Afghanistan) from the second and third centuries CE, preserve a rich artistic tradition, which conveys a didactic narrative cycle. Examples are known in both the vertical and horizontal formats. A set of vertically displayed scenes can be seen on a stele in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Scenes from the “Life of the Buddha”, Gandhara, Pakistan, Kushan period, between the 1st century and 322 CE, grey schist, courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art (Source: Transcultural Studies). At the top of this relief carving, the narration begins with the Birth scene, and what appears to be the scene of the Great Departure with the Buddha on a house leaving behind his princely life, concludes the set on the bottom. A horizontal arrangement is used on the relief at the Sackler Gallery . The two scenes illustrated here (from the original set of four) show Birth, as well as Enlightenment. Together they constitute the first two scenes of the four major events from the Buddha’s life. Since organic materials rarely survive from this time, these stone reliefs suggest that portable versions of analogous compositions, most likely rendered primarily on cotton, were also used to visually narrate the events of the Buddha’s life during this period. Scenes from the Life of the Buddha, Gandhara, Pakistan, Kushan period, between the 1st century and 322 A.D, schist, courtesy of Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington DC. (Source: Transcultural Studies). Further west, across the Asian continent in third-century Mesopotamia, the use of images for religious teachings is also documented in both Jewish and Christian contexts, suggesting that the Manichaeans were not the only ones in the region who employed didactic art in service of their mission. About ten days walking distance (ca. 270 miles=430 km) north of where Mani lived, on the Roman side of the Sasanid border, the archeological remains (discovered at Dura from the mid-third-century) preserved didactic paintings in Mesopotamian Jewish and Christian settings. The Synagogue at Dura offers a strong comparative example. Painted Baptistery, Dura-Europos, Syria, 244-45 CE, model copy, tempera on plaster, Yale University Art Gallery (Source: Transcultural Studies). Its mostly narrative scenes are large enough to be seen by a gathered congregation. The meeting hall is framed by built-in benches, orienting the community towards the center, which allows for a relatively comfortable view of all four walls. The pictorial program of such a visual library does not have to mimic the sequence of stories in the Hebrew Bible. The rabbi brings the images up as he sees fit. He may verbally refer or physically point to them when necessary. The Baptistery at Dura seems to document an analogous case with scenes such as Healing the Paralytic, Walking on Water, Woman at the Well, and Finding the Empty Tomb. Painted Synagogue, Dura-Europos, Syria, 244-45 CE, rebuilt original, tempera on plaster, Damascus National Museum (Source: Transcultural Studies). At this early era of Christianity, baptism was performed mostly for adults and, thus, it is conceivable that the ritual included a didactic component. In this small chapel, the scenes seem to be selected for their appropriateness for a baptism ritual. At the same time, they constitute part of a didactic visual library. During this time in West Asia, the itinerant Manichaean priesthood employed a portable medium (a scroll, according to Ephrem), but they also had a collection of didactic paintings during the mid-third-century, analogously similar to the Christian and Jewish communities of Mesopotamia. Textual sources confirm that the Manichaeans found their collection of didactic painting important enough to be added to their canon in a solely pictorial volume, which they labeled Mani’s Picture and later, Mani’s Picture-Book. While it is possible that the idea of using didactic art as a visual aid to oral instruction came to Mani as a result of seeing portable pictorial tableaus in India, it is also possible that using portable art in the context of oral performances was a broader, regional, West Asiatic, artistic phenomenon widely employed in both secular and religious settings in this primarily Iranian part of the late ancient world. This line of reasoning would also present an explanation as to why the collection of Manichaean didactic paintings featured so prominently during the fourth century in both Ephrem’s Mesopotamian Syriac polemical accounts, and the Coptic translations of Mesopotamian Manichaean literature, but was unknown to Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) only a century later in Roman North Africa. Despite being a lay follower of Mani for about twelve years, Augustine never mentions Mani’s Picture-Book and specifically states in his Contra Faustum that the Manicheans that Augustine knew did not illustrate their teachings nor depict their gods in any visual form.[34] Conclusion Displaying and explaining images in the course of oral instructions of religious teachings is a phenomenon best known today from the Japanese Pure Land Buddhist practice called etoki. In the course of etoki, a priest or a learned layperson stands next to a large hanging or hand scroll that contains a variety of scenes and points to the images as her elucidation proceeds. This phenomenon is documented among a variety of historical Buddhist communities, not only in East Asia, but in Central and South Asia, too. The earliest known use of such didactic art in Buddhist context is from the second and third centuries CE, when in Kushan Empire, especially in the region of Gandhara (today’s Kandahar region of Afghanistan and Peshawar region of Pakistan), narrative images on the Buddha’s life were first portrayed in art and recorded in writing. From their earliest history in mid third-century Sasanid Mesopotamia, Manichaean communities also employed didactic images that were displayed for a group of devotees as part of orally delivered teachings. They covered themes such as the duality of light and darkness, Manichaean prophets and deities, and visions of a religious universe and human salvation. Future research may reveal evidence on an analogous use of didactic art in late ancient Mesopotamia by Jewish and Christian communities. However, compared to all other religions that employed didactic images to accompany instruction, the Manichaeans were unique in three ways: (1) they consciously used such didactic art as part of their mission from the earliest days of their tradition, (2) they collected these paintings in a solely pictorial “volume” that they attributed to the founder of their religion (calling it Mani’s Picture or Picture-Book), and (3) they added this solely pictorial work to their official canon. The canonical status contributed to the preservation of Manichaean didactic art and to the custom of teaching with them throughout most of this religion’s 1400-year history. As Mani’s teachings began to be disseminated outside southern Mesopotamia across the Asian continent (already by Mani himself), it became necessary to communicate transculturally with the aid of various means of missionary adaptation. Not unlike the translation of Manichaean texts, the paintings also underwent certain changes in their format, style, and iconography in order to efficiently convey Mani’s message to its intended new audience. Accordingly, while the overall repertoire of Manichaean didactic paintings looked different from one another in Sassanid Iran, Byzantine West Asia, Uygur Central Asia, and Song- or Yuan-dynasty China, it did preserve a distinctly Manichaean religious content. Maintaining a Manichaean version of etoki required clearly comprehensible pictorial communication that was suitable as a visual aid to illustrate the religion’s teachings in distinct cultural settings. Because Manichaeism endured much persecution and is now an extinct world religion, only bits and pieces of information about its historical practices survive today. Thus, the study of Manichaean texts and art requires painstaking scholarly work in order to uncover, analyze, and interpret the available sources. The attempt to understand the artistic and textual data on the Manichaeans’ illustrated instruction, and the pictorial tools employed for it, is no exception. The ongoing research project that I was invited to report on in the above study relies on both textual and pictorial Manichaean data that are contextualized in light of comparative non-Manichaean examples in order to uncover for the first time a prominent tradition that motivated the creation, use, and preservation of pictorial art as a distinct component of religious life. Footnotes