The article below by John Palmer “Zoroaster – forgotten prophet of the one God” first appeared in The Guardian on July 13, 2010.

John Palmer is a former European editor of the Guardian and former political director of the European Policy Centre. He is visiting practitioner fellow at Sussex University’s European Institute and a member of the governing council of the Federal Trust (Photo Source: The Guardian).

John Palmer is a former European editor of the Guardian and former political director of the European Policy Centre. He is visiting practitioner fellow at Sussex University’s European Institute and a member of the governing council of the Federal Trust (Photo Source: The Guardian).

Kindly note that the embedded photographs and captions below do not appear in the original article in the Guardian; these have been cited in Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division, Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006, University of Southern California and the University of Yerevan (Iranian Studies Department).

============================================================

The tiny world wide communities of Zoroastrians are no doubt pleased to get any mention in their belief – even if it is only to provide alphabetical balance to a list starting with the Bahá’ís. Even those who take a close interest in the more exotic or esoteric of religions tend to have a vague grasp on what the followers of the ancient Persian (or maybe Bactrian) prophet, Zarathustra (Zoroaster in Greek) – born around 800 BC – actually believed. This is a great pity since even a non-believer must be impressed with the evidence of how the religious ideas first expressed by Zoroaster were fundamental in shaping what emerged as Judaism after the 5th century BC and thus deeply influenced the other Abrahamic religions – Christianity and Islam.

Archaeologists in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region have discovered major Zoroastrian tombs, dated to over 2,500 years ago. (Caption and Photo Source: Chinanews.com). As noted in the China News report: “This is a typical wooden brazier found in the tombs. Zoroastrians would bury a burning brazier with the dead to show their worship of fire. The culture is unique to Zoroastrianism…This polished stoneware found in the tombs is an eyebrow pencil used by ordinary ladies. It does not just show the sophistication of craftsmanship here over 2,500 years ago, but also demonstrates the ancestors’ pursuit of beauty, creativity and better life, not just survival. It shows this place used to be highly civilized”. For more on this topic see: Archaeologists uncover Zoroastrian Links in Northwest China

Archaeologists in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region have discovered major Zoroastrian tombs, dated to over 2,500 years ago. (Caption and Photo Source: Chinanews.com). As noted in the China News report: “This is a typical wooden brazier found in the tombs. Zoroastrians would bury a burning brazier with the dead to show their worship of fire. The culture is unique to Zoroastrianism…This polished stoneware found in the tombs is an eyebrow pencil used by ordinary ladies. It does not just show the sophistication of craftsmanship here over 2,500 years ago, but also demonstrates the ancestors’ pursuit of beauty, creativity and better life, not just survival. It shows this place used to be highly civilized”. For more on this topic see: Archaeologists uncover Zoroastrian Links in Northwest China

Born at a time when the peoples of the Iranian plateau were evolving a settled agriculture, Zoroaster broke with the traditional Aryan religions of the region which closely mirrored those of India, and espoused the idea of a one good God – Ahura Mazda. What became known eventually in the west as Zoroastrianism was also the first to link religious belief with profound attachment to personal morality. In Zoroastrian eschatology there is much which has become familiar from reading the Jewish and Christian testaments: heaven, hell, redemption, the promise of a Sashoyant (Messiah), the existence of an evil spirit Ahriman and – most striking of all – the prospect of a final battle for the salvation of man at “the end of time” between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman leading to the latter’s final defeat.

The main contact between westerners and Zoroastrians came in India where they were known as Parsees (Persians), descendants of those who took part in a large scale migration from Persia after the Muslim conquest of that country. Zoroastrians were held (quite wrongly) to worship fire because they kept a permanent flame in their temples. Some even questioned whether they were monotheists at all because Ahriman was referred to as an evil “god”. But all the Abrahamic religions have also struggled to explain “evil” in the world which is why they gave Satan an important role. The first encounter between the ancient peoples who developed historical Judaism and the Persian religious ideas of Zoroastrianism seems to have come either during or shortly after the captivity in Babylon. It was the Persian king of kings, Cyrus, who liberated the Hebrews from Babylon and one of his successors, Darius, who organised and funded the return of some of the captives (probably along with many Persians) to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem. Nehemiah and Ezra also reorganised the traditional religion of the Judaeans and Israelites. What emerged was a stricter monotheistic version which was consistent with basic beliefs of the Persian imperial religion – Zoroastrianism. Those who might doubt how Persian imperial policy so decisively shaped what we know as Judaism should reflect on the remarkable and first ever declaration of belief in one, universal God by the biblical writer known as “Second Isaiah” during this period. Indeed Isaiah describes King Cyrus as a “Messiah” and the chosen instrument of Yahweh. Interestingly there is evidence that the Persian imperial policy towards the religion of their subject peoples – to allow the traditional name of their gods to be retained but to revise the religions themselves in the image of Zoroastrianism – was also applied in Babylon and Egypt as well as Palestine. Some claim that a belief in monotheism in Judea developed a little before the Babylonian conquest and exile. But although there is evidence for a centralisation of the different Canaanite-style cults into the worship of Yahweh in the capital – Jerusalem – over this period the most which can be said was that a form of monolatry, a belief in one God for a particular people had emerged. The Persian influence on Judaism was powerful and long lasting. Certainly the profound belief in the end of days exhibited by the Dead Sea Scroll communities in the immediately pre-Christian era and indeed the images employed by the Christian evangelist, John, in his Apocalypse, display a clear continuity of influence. What – at the very least – were the deep affinities between Zoroastrianism and Judaism goes a long way to explain what over the centuries were the close and friendly relations between Persians and Jews. The influence of 20th century religious-political ideologies have poisoned that relationship. Perhaps a greater acknowledgement by Jews, Christians and Muslims of their Persian Zoroastrian inheritance would be a step to improving those relationships.

A detail of the painting “School of Athens” by Raphael 1509 CE (Source: Zoroastrian Astrology Blogspot). Raphael has provided his artistic impression of Zoroaster (with beard-holding a celestial sphere) conversing with Ptolemy (c. 90-168 CE) (with his back to viewer) and holding a sphere of the earth. Note that contrary to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm, the “East” represented by Zoroaster, is in dialogue with the “West”, represented by Ptolemy. Prior to the rise of Eurocentricism in the 19th century (especially after the 1850s), ancient Persia was viewed positively by the Europeans. For more information see: Dr. Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster – The First Universalist

A detail of the painting “School of Athens” by Raphael 1509 CE (Source: Zoroastrian Astrology Blogspot). Raphael has provided his artistic impression of Zoroaster (with beard-holding a celestial sphere) conversing with Ptolemy (c. 90-168 CE) (with his back to viewer) and holding a sphere of the earth. Note that contrary to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm, the “East” represented by Zoroaster, is in dialogue with the “West”, represented by Ptolemy. Prior to the rise of Eurocentricism in the 19th century (especially after the 1850s), ancient Persia was viewed positively by the Europeans. For more information see: Dr. Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster – The First Universalist

“St. Augustine of Hippo in his Study” as portrayed in 1480 by Sandro Botticelli (Source: Public Domain). Interestingly, St. Augustine had been a Manichean for 9 years until his conversion to Christianity in the aftermath of Emperor Diolectian’s edict (284-305 CE) condemning the Manicheans. Despite his conversion, it is believed that St. Augustine’s Manichean past influenced his later Christian writings. For more information on Manichean beliefs, see: Mani: Forgotten Prophet of Ancient Persia

“St. Augustine of Hippo in his Study” as portrayed in 1480 by Sandro Botticelli (Source: Public Domain). Interestingly, St. Augustine had been a Manichean for 9 years until his conversion to Christianity in the aftermath of Emperor Diolectian’s edict (284-305 CE) condemning the Manicheans. Despite his conversion, it is believed that St. Augustine’s Manichean past influenced his later Christian writings. For more information on Manichean beliefs, see: Mani: Forgotten Prophet of Ancient Persia

The West Wall in Jerusalem. After his conquest of Babylon, Cyrus allowed the Jewish captives to return to Israel and rebuild the Hebrew temple. It is believed that approximately 40,000 did permanently return to Israel. For more discussion on this topic see: Retort to Daily Telegraph article against Cyrus the Great

The West Wall in Jerusalem. After his conquest of Babylon, Cyrus allowed the Jewish captives to return to Israel and rebuild the Hebrew temple. It is believed that approximately 40,000 did permanently return to Israel. For more discussion on this topic see: Retort to Daily Telegraph article against Cyrus the Great

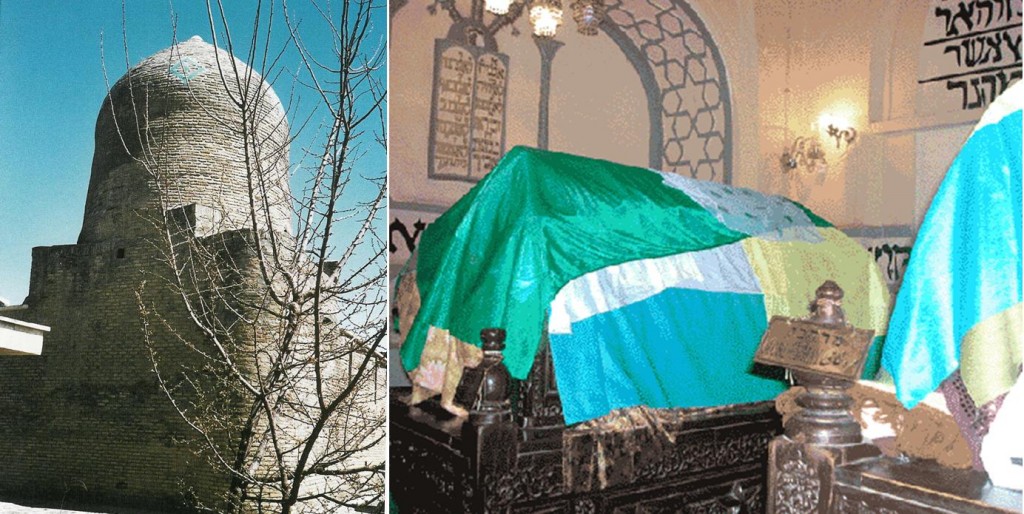

The tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamedan, northwest Iran. External view (left) and the interior of the tomb (right). For more see: Response to Spiegel Magazine’s attack on the Legacy of Cyrus the Great

The tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamedan, northwest Iran. External view (left) and the interior of the tomb (right). For more see: Response to Spiegel Magazine’s attack on the Legacy of Cyrus the Great

Iranian Jews praying during Hanukkah celebrations on Tuesday, December 27, 2011 at the Yousefabad Synagogue, in Tehran, Iran (Source: Wodu). For more on this topic see: Professor Jacob Neusner: Persian Elements in Talmud

Iranian Jews praying during Hanukkah celebrations on Tuesday, December 27, 2011 at the Yousefabad Synagogue, in Tehran, Iran (Source: Wodu). For more on this topic see: Professor Jacob Neusner: Persian Elements in Talmud